Hau, mitakolapi. . . . The strangest thing about this project: my old Mac Powerbook's keyboard is so old that I can't tell the "I" from the "O" (and no, I'm not a touch-typist). So there I was, trying

to type "Sacred Pipe" over and over again—and it kept coming out as "Sacred Pope."

.gif) |

INTRODUCTION, with Lakota Language Notes:

White Buffalo (Calf) Woman = Ptesan [ptay-SAH(n)] Winyan [WEE(n)yah(n)] . . . (Note also that, when pronouncing such common phrases as "one word," the Lakota accent usual shifts to the second syllable: Ptay-SAHn-wee[n]-yah[n]):

pte = female buffalo (buffalo cow); san = gray, whitish; winyan = woman

Alternative spellings/versions include Pte San Winyan, Pte San Win (quite common: the vernacular version if you will),

Ptehincala San Win (Ptehincala [ptay-HEE(n)-chah-lah] = buffalo calf).

White Buffalo Woman is often regarded as a manifestation/avatar of Wohpe [woh'PAY]: (most literally) Falling Star, or

Meteor; aka Beautiful Woman. (Indeed, possessed of both beauty and wisdom, she's rather a combination of Aphrodite and Athena.) And because

she's the daughter of Shkan, the Sky, she is also known as Mediator (i.e., between heavens & earth). As another "woman

who falls from the sky" of sorts, Wohpe may be seen as rather analogous to the well-known Iroquois mythic figure, Sky Woman.

In another story, White Buffalo Woman is one of the seven star-sisters of the Pleiades, in a Lakota legend similar to Momaday's oft-told Kiowa

tale about Devil's Tower and the bear-fleeing seven sisters (who become the stars of the Big Dipper instead of the Pleiades).

|

One succinct version of the main story: One succinct version of the main story:

It was a hard winter. Game was scarce, and the People were slowly starving. Two warriors walked out onto the plains, and saw a beautiful woman there, wearing a robe of white buffalo skin embroidered with beads. Seeing this woman walking alone, one man had a bad thought about her. "We can have our way with her," he said to the other, "and no one will know." The other warrior disagreed. "We will treat this woman with respect." But the first warrior approached the woman, and put out his hand to touch her. As he did so, dust swirled up around him, and when it was gone, nothing remained of the warrior but his bones, picked clean. The woman looked at the other man and said, "Do not be afraid. You have good thoughts and a good heart. You will be a messenger for your People. Tell them I will come in four days, and bring them a gift from Creator."

In four days, the People gathered together in the largest tipi. The woman in white appeared among them, carrying a bundle. It was a chanupa [pipe] made of pipestone and wood, with twelve eagle feathers hanging from the stem. She gave it to the People, and she explained, "The smoke of this pipe will carry your prayers directly to Creator. When you hold this pipe, you must speak nothing but the truth, for it is very powerful." She taught them seven sacred ceremonies they would practice with the chanupa, of which the inipi, the sweat lodge, is one. And then she took her leave of the People, saying "Toksha ake wacinyanktin ktelo"—I will see you again.

They all gathered to watch her go, and they saw as she lay down on the ground, rolled, and then stood up again in the shape of a black buffalo calf. She walked a little way and lay down, and this time she was a yellow buffalo calf. She walked a little way and lay down, and this time she was a red buffalo calf. She walked a little way and lay down, and this time she was a white buffalo calf. In this form she trotted over the plains and disappeared.

—from Turtle Island: the Mythology of North America

.gif) from "WHITE BUFFALO CALF WOMAN Brings The First Pipe; As told by John Fire Lame Deer, in 1967" (Arvol Looking Horse/Paula Giese): from "WHITE BUFFALO CALF WOMAN Brings The First Pipe; As told by John Fire Lame Deer, in 1967" (Arvol Looking Horse/Paula Giese):

The Sioux are a warrior tribe, and one of their proverbs says, "Woman shall not walk before

man." Yet White Buffalo Woman is the dominant figure of their most important legend. The medicine man Crow Dog explains,

"This holy woman brought the sacred buffalo calf pipe to the Sioux. There could be no Indians without it. Before she came,

people didn't know how to live. They knew nothing. The Buffalo Woman put her sacred mind into their minds." [What a wonderful expression.] At the ritual of

the Sun Dance one woman, usually a mature and universally respected member of the tribe, is given the honor of respresenting [sic] Buffalo Woman.

Though she first appeared to the Sioux in human form, White Buffalo Woman was also a buffalo—the Indians'

brother, who gave its flesh so that the people might live. Albino buffalo were sacred to all Plains tribes; a white buffalo hide was

a sacred talisman, a possession beyond price. [emphases in bold throughout: TCG]

|

| | .gif) * TCG's Points of Interest (most developed in more detail in the bibliographical annotations below): * TCG's Points of Interest (most developed in more detail in the bibliographical annotations below):

| | | 1) The White Buffalo Calf Woman is . . . a woman. Thus reading her as proto-feminist figure and/or a "vestige" of a previously more gynocentric Lakota religion & society is an attractive possibility. (In this regard, see P. G. Allen, and others, below.)

|

| | 2) The White Buffalo Calf Woman is also . . . another animal species. The tatanka oyate (buffalo nation or people [also: pte oyate]) were of course the Lakotas' main food source, and from a feminist point of view, it's interesting that White Buffalo Woman not

only brings the Sacred Pipe (and social stability), but also food—that is, her own buffalo corporality. (Both food-bringer and food, hmmm: comparative religion scholars and neo-Freudians could go wild here.) More interestingly to an eco-theorist like me, the myth also reflects a species interrelationship

rather alien to our Western worldview, a veritable interchangeability of species, a permeability of identity (referring to her final transformation "back" into a buffalo), that arises from a much more egalitarian attitude towards other animals. (Yes, the Lakota are an oyate, but so are the buffalo, the eagles [wanbli], et al.)

|

| | 3) You shouldn't try to pin down some definitive version of the "White Buffalo Calf Woman

Brings the Pipe to the People" story—there isn't one. Vine Deloria, Jr. notes that this is, in fact, one crucial difference between

Western-Civ. theology's origin myths and those of Native "religions": the latter embrace the diversity/multiplicity of versions, and appreciate the

socio-evolutionary fact that the stories—the tellings—change with the time & the people. (This is in contrast to, Deloria pointedly

notes, Western religions' emphasis on the BOOK set in stone for all time, as it were. Not to get too inflammatory here, but I think that the Jewish religion began as a fine tribe-and-place-specific religion, too; it was when Christianity tried to make it a creed for all peoples, places, and times that the shite hit the fan.)

|

| | 4) I'm actually relieved that I couldn't recall, or find, a whole lot of literary appeals to the

White Buffalo Calf Woman on the part of non-"Sioux" Native writers. While not on the level of Ted Nugent writing songs about the white buffalo

[see below], this, too, might be considered a form of cultural appropriation. (Cf. Sherman Alexie's

satire of his various Spokane/Coeur d'Alene characters' obsession with the Lakota warrior, Crazy Horse. As Thomas Builds-the-Fire

quips in Smoke Signals, "But our tribe never hunted buffalo. We were fishermen." . . . Gerald Vizenor has also noted

the incongruity of various Minnesota Ojibwe A.I.M. leaders in the early 1970's flocking to Pine Ridge & Leonard Crow Dog to "get some [Lakota] religion.") To put it another way, tribal sovereignty should extend to a tribe's culture, including its spirituality.

|

| | 5) As evidence for Deloria's claim that Native/Lakota religion keeps changing (and should keep changing) with the times, it's fascinating to compare Sneve's grandma's rendition of WBW with that of Mary Brave Bird. The former seems very early 20th-c. Euro-American "Stand by Your Man"; the latter

is an earnest (Euro-American!?) anger at contemporary Lakota males' lack of appreciation for the Lakota culture's female/feminist origins. (Which brings up the tried-and-true New Historicist question, how can any such "versions" be truly representative of WBW in her traditional origins? This question also encompasses the modern pictorial versions of WBW at the top of this page.)

|

| | 6) Not to steer budding journalists in a specific direction, but I'd be interested in how/where you see the power (wakan) of White Buffalo Woman at work in Lakota culture today, if at all:

in a still largely "matriarchal" family dynamics? In strong women such as former Pine Ridge tribal president Cecelia Fire Thunder?

(Unfortunately, the tribal people who reacted against Fire Thunder's policies represented, in one sense, a reactionary return to a traditional patriarchalism. Given the centrality of WBW in Lakota ceremonial lore, there is great irony here.) (Even more ironic is that my #5 and #6 points are based upon rather contradictory assumptions/methodologies. I'm sorry, but that's what happens when a crossblood fellow gets influenced as much by Nietzsche as Crazy Horse.)

|

.gif) BIBLIOGRAPHY BIBLIOGRAPHY |

|---|

| TRADITIONAL (Male) SOURCES (earliest dates): |

Black Elk, Nicholas {Oglala Lakota}, and John G. Neihardt. "The Offering of the Pipe." Black Elk Speaks: Being the Life Story of a Holy Man of the Oglala Sioux [1932]. Lincoln: U of Nebraska P, 2004. 1-5.

Black Elk, Nicholas {Oglala Lakota}, and John G. Neihardt. "The Offering of the Pipe." Black Elk Speaks: Being the Life Story of a Holy Man of the Oglala Sioux [1932]. Lincoln: U of Nebraska P, 2004. 1-5. |

| |

—Perhaps the most well-known version of the White Buffalo Calf

Woman story, given this book's longtime good sales figures and ubiquity in college classrooms.

Significantly, Black Elk begins this "story of his life" not with his individual life, but with

that of the people, the Lakota oyate, with a foundational story of tribal community. Black Elk

never names the woman, simply referring to her as "a sacred woman" or as "the beautiful young woman."

—Perhaps the most well-known version of the White Buffalo Calf

Woman story, given this book's longtime good sales figures and ubiquity in college classrooms.

Significantly, Black Elk begins this "story of his life" not with his individual life, but with

that of the people, the Lakota oyate, with a foundational story of tribal community. Black Elk

never names the woman, simply referring to her as "a sacred woman" or as "the beautiful young woman."

|

|

Black Elk, Nicholas.

Black Elk, Nicholas. "The Offering of the Pipe." The Sacred Pipe: Black Elk's Account of the Seven Rites of the Oglala Sioux [1953]. Ed. Joseph Epes Brown. Norman: U of Oklahoma P, 1989. 3-9. "The Offering of the Pipe." The Sacred Pipe: Black Elk's Account of the Seven Rites of the Oglala Sioux [1953]. Ed. Joseph Epes Brown. Norman: U of Oklahoma P, 1989. 3-9.

|

| | —Black Elk's account

here is much more detailed, although Brown's erudite footnote attempts to connect Lakota spirituality with Hinduism

are pretty hard to stomach. As in BES, the White Buffalo Woman is not named; she is called the "wakan

woman." (Brown translates wakan as "holy" or "sacred"; I'd prefer "of power," as in "woman of power.")

|

|

Finger {Oglala Lakota}. "Wohpe and the Gift of the Pipe" [1914]. Lakota Belief and Ritual. Comp. James R. Walker. Ed. Raymond J. DeMallie and Elaine A. Jahner. Lincoln: U of Nebraska P, 1991. 109-112.

Finger {Oglala Lakota}. "Wohpe and the Gift of the Pipe" [1914]. Lakota Belief and Ritual. Comp. James R. Walker. Ed. Raymond J. DeMallie and Elaine A. Jahner. Lincoln: U of Nebraska P, 1991. 109-112.

|

| | —Finger, like Black Elk, was an Oglala Lakota

wicasha wakan ("medicine man"). Walker gives "Beautiful Woman" as the English rendition of Wohpe. According to Finger, "Wohpe would be present in the smoke of any such pipe if smoked with proper solemnity and form" (111-112). . . . (By the way,

this version is also significant in its inclusion—with footnotes by yours truly—in the latest Bedford Anthology of American Literature [Vol. 1].)

|

|

Standing Bear {Oglala Lakota}.

Standing Bear {Oglala Lakota}. Land of the Spotted Eagle [1933]. Lincoln: U of Nebraska P, 1978. Land of the Spotted Eagle [1933]. Lincoln: U of Nebraska P, 1978.

|

| | —Standing Bear's version of the tale (pp. 220-222) seems much more Christianized than those of Finger and Black Elk. She is called "Holy Woman" and even provides the people with a version of the Ten Commandments.

|

| |

|

REINSCRIPTIONS BY (mostly) NATIVE WOMEN: |

Allen, Paula Gunn {Laguna Pueblo/Lakota}.

Allen, Paula Gunn {Laguna Pueblo/Lakota}. The Sacred Hoop: Recovering the Feminine in American Indian Traditions. Boston: Beacon, 1986. The Sacred Hoop: Recovering the Feminine in American Indian Traditions. Boston: Beacon, 1986.

|

| | —Among the characteristics of "American Indian literature" that Allen presents in her Introduction are the following:

|

| |

3. Traditional tribal lifestyles are more often gynocratic than not, and they are never patriarchal[?!].

3. Traditional tribal lifestyles are more often gynocratic than not, and they are never patriarchal[?!].

4. The physical and cultural genocide of American Indian tribes is and was mostly about patriarchal fear of gynocracy. . . . But colonial attempts at cultural genocide notwithstanding, there were and are gynocracies—that is, woman-centered tribal societies in which matrilocality, matrifocality, matrilinearity, maternal control of household goods and resources, and female deities of the magnitude of the Christian God were and are present and active features of traditional tribal life.

6. Western studies of American Indian tribal systems are erroneous at base because they view tribalism from the cultural bias of patriarchy and thus either discount, degrade, or conceal gynocratic features or recontextualize those features so that they will appear patriarchal. (2-4) (Truly a brilliant [and I think, specious] argument here: if no evidence of matriarchy can be found regarding a particular tribe, PGA can claim that it's all been effaced by Western patriarchy.)

|

|

| | —While Allen's book concentrates on desert-southwest Native deities more commonly discussed as gynocentric, such as Thought Woman and Yellow Woman of the Pueblo, she does find a common thread in White Buffalo Woman:

|

| |

|

The idea that Woman is possessed of great medicine power is elaborated in the Lakota myth of White Buffalo Woman. She brought the Sacred Pipe to the Lakota, and it is through the agency of this pipe that the ceremonies and rituals of the Lakota are empowered. Without the pipe, no ritual magic can occur. According to one story about White Buffalo Woman, she lives in a cave where she presides over the Four Winds. In Lakota ceremonies, the four wind directions are always acknowledged, usually by offering a pipe to them. The pipe is ceremonial, modeled after the Sacred Pipe given the people by the Sacred Woman. The Four Winds are very powerful beings themselves, but they can function only at the bidding of White Buffalo Woman. The Lakota are connected to her still, partly because some still keep to the ways she taught them and partly because her pipe still resides with them. (16-17)

|

|

|

Allen, Paula Gunn. "What Is Wakan." Grandmothers of the Light: A Medicine Woman's Sourcebook. Boston: Beacon Press, 1992. 125-132.

Allen, Paula Gunn. "What Is Wakan." Grandmothers of the Light: A Medicine Woman's Sourcebook. Boston: Beacon Press, 1992. 125-132.

|

| | —A more extended treatment of the White Buffalo Woman story by Allen, but I haven't read it yet. Apparently it's part of PGA's later turn to—well, New Age "kookiness"; according to one publisher's blurb, "she claims to channel the teachings of Native American goddesses."

|

|

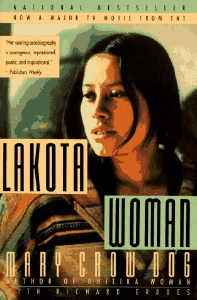

[Brave Bird, Mary =>] Crow Dog, Mary {Oglala Lakota}, and Richard Erdoes. Lakota Woman. New York: HarperPerennial, 1990.

[Brave Bird, Mary =>] Crow Dog, Mary {Oglala Lakota}, and Richard Erdoes. Lakota Woman. New York: HarperPerennial, 1990.

|

| | —Brave Bird's irreverent, in-your-face tone serves her well as she relates her experiences in the American Indian Movement, etc. (The book

was published under her married name; she was married to the wicasha wakan Leonard Crow Dog, one of the "medicine men" the AIMsters befriended when they came to Pine Ridge in the early 1970's.) Especially interesting are her perceptions regarding contemporary Lakota gender roles:

|

| |

There is a curious contradiction in Sioux society. The men pay great lip service to the status women hold in the tribe. Their rhetoric on the subject is beautiful. They speak of Grandmother Earth [Unci Maka] and how they honor her. Our greatest cultural hero—or rather heroine—is the White Buffalo Woman, sent to us by the Buffalo nation, who brought us the sacred pipe and taught us how to use it. . . .

There is a curious contradiction in Sioux society. The men pay great lip service to the status women hold in the tribe. Their rhetoric on the subject is beautiful. They speak of Grandmother Earth [Unci Maka] and how they honor her. Our greatest cultural hero—or rather heroine—is the White Buffalo Woman, sent to us by the Buffalo nation, who brought us the sacred pipe and taught us how to use it. . . .

We had warrior women in our history. Formerly, when a young girl had her first period, it was announced to the whole village by the herald, and her family gave her a big feast in honor of the event, giving away valuable presents and horses to celebrate her having become a woman. Just as men competed for war honors, so women had quilling and beading contests. The woman who made the most beautiful fully beaded cradleboard won honors equivalent to a warrior's coup. The men kept telling us, "See how we are honoring you . . ." Honoring us for what? For being good beaders, quillers, tanners, moccasin makers, and child-bearers. That is fine, but . . . In the governor's office at Pierre [SD] hangs a big poster put up by Indians. It reads:

WHEN THE WHITE MAN

DISCOVERED THIS COUNTRY

INDIANS WERE RUNNING IT—

NO TAXES OR TELEPHONES.

WOMEN DID ALL THE WORK—

THE WHITE MAN THOUGHT

HE COULD IMPROVE UPON

A SYSTEM LIKE THAT.

If you talk to a young Sioux about it he might explain: "Our tradition comes from being warriors. We always had to have our bow arms free so that we could protect you. That was our job. . . . That is our tradition."

"So, go already," I tell them. "Be traditional. Get me a buffalo!"

They are still traditional enough to want no menstruating woman around [i.e., a taboo]. But the big honoring feast at a girl's first period they dispense with. For that they are too modern. (65-67)

* * *

It was an Indian woman who gave it [the American Indian Movement] its name. She told me, "At first we called ourselves 'Concerned Indian Americans' until somebody discovered that the initials spelled CIA. That didn't sound so good. Then I spoke up: 'You guys all aim to do this, or you aim to do that. Why don't you call yourselves AIM, American Indian Movement?' And that was that." (76)

|

|

|

Brave Bird, Mary, and Richard Erdoes. Ohitika Woman. New York: Grove, 1993.

Brave Bird, Mary, and Richard Erdoes. Ohitika Woman. New York: Grove, 1993.

|

| | —This is the sequel to Lakota Woman, obviously. (Ohitika means "Brave.")

|

| |

[BB is discussing her membership in the Native American Church (a Native-Christian syncretism) and the "All-mother of the Universe":] There is a parallel to her in the legend of Ptesan Win, the White Buffalo Calf Woman, who brought the sacred pipe to the Sioux Nation. It pleases me, and strengthens me in some strange way, to see women playing such a central role in Indian religion. (71)

* * *

Looking back, I have to say that Leonard Crow Dog, in his own strange way[!], is a great man. He has somehow created a pan-Indian belief. You could call it a religion in which it no longer matters whether . . you believe in the White Buffalo Calf Woman or the Corn Maiden, whether you perform the Pueblo cloud dance or the Sioux sun dance. [I'm agin' it!] Of course, he is always the traditional Lakota medicine man, doing the ancient Sioux ceremonies exactly how they should be done, but he has been a uniting force for all[?] Native Americans and you can't take that away from him. (92-93) [Deloria actually performs a similar pan-Indian gesture in his introduction to a recent edition of Black Elk Speaks, offering it as a Native "bible" for all Native youths.].

* * *

On the one hand, Lakota society was male-oriented, as is usual among tribes of nomadic hunter-warriors. It is among the sedentary corn-planting pueblos that society is women-oriented. [Rather a refutation of PG Allen (below), by the way.] . . . [But:] Women were more honored among us than among whites. During much of the nineteenth century, many American women did not have the right to own property. Our women always did. The tipi belonged to the wife, just as in the southwestern pueblos the house belonged to the woman. . . .

If the Sioux of old were male chauvinists on one side, they were feminists on the other. They prayed to Wakan Tanka, whom they also called Tunkashila, the Grandfather Spirit. [However, I would claim that in the truest, "mystical" sense, wakantanka, the "big(gest) power," is ungendered. The "Grandfathers" are merely one manifestation thereof.] But the most important supernatural being in their mythology was Ptesan Win, the White Buffalo Calf Woman, who brought the sacred pipe to the Lakota, taught them its use, taught them, as a matter of fact, how to live as human beings. . . .

It is said that the White Buffalo Calf Woman dazzled humans with her unearthly beauty. In some tales, she appears to the hunters as a young girl in a shining white buckskin dress, and in others as naked, clothed only in her flowing raven hair. When she leaves the tribe, after teaching them all they need to know, she transforms herself into a white buffalo calf, symbolizing the close relationship between the people and this holy animal, who gave of itself[!] so that the humans could live, whose skull is our sacred altar. . . .

There have always been strong women among us. As a Cheyenne [a tribe closely allied to the Lakota] proverb puts it: "As long as the hearts of our women are high, the nation will live. But should the hearts of our women be on the ground, then all is lost." (180-184)

* * *

Women are now beginning to fight this situation [domestic violence]. They go into tribal politics. They are not afraid to put a restraining order on violent men. They give strength to each other. We have the White Buffalo Woman Society at Rosebud [SD], and the Sacred Shawl Society in Pine Ridge. The White Buffalo Woman Society was founded in 1979 by Tillie Black Bear, herself a victim of domestic violence. (190)

|

|

|

Harjo, Joy {Muskogee/Cherokee}.

Harjo, Joy {Muskogee/Cherokee}. "Deer Dancer." In Mad Love and War. Hanover: Wesleyan UP, 1990. 5-6. "Deer Dancer." In Mad Love and War. Hanover: Wesleyan UP, 1990. 5-6.

|

| | —Harjo—perhaps the most famous Native

woman poet writing today—revives White Buffalo Woman in this prose poem, in a characteristic intertwining of the mythic and mundane, the sacred and

the secular: "She was the myth slipped down through dreamtime." The poem's multivocal perspectivism allows the reader to interpret the appearance of the mythic figure as either drunken illusion or

"magical" intervention in the real world. (As in Silko's stories, the best response is to keep both possibilities in mind.) The "deer woman" here

is a thus both a real woman walking into a sordid bar and a spirit performing a ceremonial return of the "divine":

|

| |

The woman inside the woman who was to dance naked in the bar of misfits blew deer magic. Henry Jack, who could not survive a sober day, thought she was Buffalo Calf Woman come back, passed out, his head by the toilet. All night he dreamed a dream he could not say. The next day he borrowed money, went home, and sent back the money I lent. Now that's a miracle. Some people see vision in a burned tortilla, some in the face of a woman.

|

|

|

Harjo, Joy. The Woman Who Fell from the Sky. New York: Norton, 1994.

Harjo, Joy. The Woman Who Fell from the Sky. New York: Norton, 1994.

|

| | —While not an explicit treatment of White Buffalo

Woman, Harjo's reinscription of Sky Woman of Iroquois legend is quite appropriate in context. Like Wohpe/Falling Star, Sky Woman is

invoked as a strong woman deity, an intervening "Mediator" in a postmodern world that has gone awry, that has (to use one of Harjo's

most important & loaded words) "forgotten." Besides the title poem, notable efforts include "A Postcolonial Tale," "The Myth of Blackbirds,"

and "Perhaps the World Ends Here."

|

|

Powers, Marla N.. Oglala Women: Myth, Ritual, and Reality. Chicago: U of Chicago P, 1986.

Powers, Marla N.. Oglala Women: Myth, Ritual, and Reality. Chicago: U of Chicago P, 1986.

|

| | —Powers is an anthropologist who—like her more famous

anthropologist husband, William K. Powers (Oglala Religion)—has spent many years studying "among" the Oglala Lakota (i.e., Pine Ridge Rez):

|

| |

Even though from a Western perspective Oglala

women are portrayed as subordinate to men—particularly in matters pertaining to politics, economics, and religion—women have

fared much better in the cosmological realm, where even non-Indians agree that woman reigns supreme. . . . [I]t is a sacred woman

who drops to earth in the form of a falling star and unites with the most virile of sacred beings, the South Wind. In the transformation of

Falling Star into the sacred White Buffalo Calf Woman, she brings to a starving Lakota nation that instrument of prayer, the Calf Pipe

. . . . (35)

* * *

The woman Wohpe is particularly important [in Lakota mythology] . . . because it is this female who, after the emergence of the Pte

Oyate, 'Buffalo Nation' from their subterranean homes will be transformed into the sacred Ptehincalasan Win 'White Buffalo Calf Woman.'

It is this same woman who happens upon starving humans later in what are perceived to be historical times, with gifts of the sacred pipe

and the Seven Sacred Rights. Thus the transformation of Wohpe, the falling star of the cosmological past, into the White Buffalo Calf Woman

of the historical past, represents a significant continuum from old to new, symbolized most dramatically in the appearance of a single woman.

(40-41)

* * *

[Regarding controversies over meanings/origins of Lakota "religious symbols":] What is not disputed . . . is that the sacred pipe

was brought to the Lakota people by a sacred woman called Ptehincalasan Win 'White Buffalo Calf Woman.' It is also acknowledged that the

White Buffalo Calf Woman and Wohpe, Falling Star, are the same.

The coming of the sacred pipe is a story told frequently at Pine Ridge and other

Lakota reservations. But as might be expected, . . . a wide variety of stories are associated with its arrival among the

Lakotas. . . . For example, one pipe story collected by the missionary Rev. Eugene Buechel, S.J., fails to consider that

when the White Buffalo Calf Woman first appeared to the Lakota people she was nude, and one of the hunters who first saw her wanted to have sexual

relations with her. Of course the teller of the story apparently knew the priest would not take well to the sexual references and simply omitted

them[!]. (42-43)

|

| |

Silko, Leslie Marmon {Laguna Pueblo}.

Silko, Leslie Marmon {Laguna Pueblo}. "Yellow Woman and a Beauty of the Spirit." Yellow Woman and a Beauty of the Spirit. New York: Simon & Schuster, 1996. 60-72. "Yellow Woman and a Beauty of the Spirit." Yellow Woman and a Beauty of the Spirit. New York: Simon & Schuster, 1996. 60-72.

|

| | —A female deity with some similarities to WBW, the Pueblo fertility goddess Yellow Woman (Kochininako) is championed often in Silko's corpus as an epitome of

both female independence and maternal bounty:

|

| |

Kochininako, Yellow Woman, represents all women in the old stories. Her deeds span the spectrum of human behavior and are mostly heroic acts

. . . . Because Laguna Pueblo cosmology features a female Creator [Thought Woman], the status of women is equal with the

status of men, and women appear as often as men in the old stories as hero figures. Yellow Woman is my favorite because she dares

to cross traditional boundaries of ordinary behavior during times of crisis in order to save the Pueblo; her power lies in her courage and in her

uninhibited sexuality, which the old-time Pueblo stories celebrate again and again because fertility was so highly valued.

. . . . The stories about Kochininako made me aware that sometimes an individual must act despite disapproval, or concern for appearances or what

others may say. From Yellow Woman's adventures, I learned to be comfortable with my differences. . . . . Kochininako is beautiful because she has the

courage to act in times of great peril, and her triumph is achieved by her sensuality, not through violence and destruction. For these

qualities of the spirit, Yellow Woman and all women are beautiful. (70, 71, 72)

Kochininako, Yellow Woman, represents all women in the old stories. Her deeds span the spectrum of human behavior and are mostly heroic acts

. . . . Because Laguna Pueblo cosmology features a female Creator [Thought Woman], the status of women is equal with the

status of men, and women appear as often as men in the old stories as hero figures. Yellow Woman is my favorite because she dares

to cross traditional boundaries of ordinary behavior during times of crisis in order to save the Pueblo; her power lies in her courage and in her

uninhibited sexuality, which the old-time Pueblo stories celebrate again and again because fertility was so highly valued.

. . . . The stories about Kochininako made me aware that sometimes an individual must act despite disapproval, or concern for appearances or what

others may say. From Yellow Woman's adventures, I learned to be comfortable with my differences. . . . . Kochininako is beautiful because she has the

courage to act in times of great peril, and her triumph is achieved by her sensuality, not through violence and destruction. For these

qualities of the spirit, Yellow Woman and all women are beautiful. (70, 71, 72)

|

| |

Sneve, Virginia Driving Hawk {Sicangu Lakota}. Completing the Circle. Lincoln: U of Nebraska P, 1995.

Sneve, Virginia Driving Hawk {Sicangu Lakota}. Completing the Circle. Lincoln: U of Nebraska P, 1995.

|

| | —Like many Native women writers (e.g., Silko, Maria Campbell, Luci Tapahonso), Sneve writes eloquently of her connection with

Indian tradition through the stories of female elders—here, her paternal grandmother Flora:

|

| |

|

Flora used her voice well in her narrations. It never varied much in pitch or tone but ranged in volume from a near whisper to a shout. In the wavering firelight, her gestures enhanced the telling. Her head bobbed, shook, or nodded; she pursed her lips to indicate "over there"; her hands beckoned, waved, followed the lightning's zigzag and echoed the clap of thunder, or became the beat of a drum; she sat tall proudly or in anger, or she slumped in despair. [What a wonderful sentence! (TCG)] She stirred my imagination, or perhaps its was already so charged that I imagined it all.

They say [Flora's stories always began] that somewhere over by the Pipestone Quarries [in present-day Minnesota], the people gathered to pray to Wakantanka. Two young men were sent out to hunt. [. . . omission of the bulk of the tale (TCG) . . .]

She told the people about Wakantanka. She said that she was the people's sister and that she had brought them a sacred pipe. The pipe was for peace, not for war.

She talked to the women. "My sisters," she called them, "you have hard things to do in your life. You have pain when you have babies, and it's hard to raise children. But you are important, because without you there would be no people. So you will have babies for your husband. You will feed your man and children; you will make their clothes; you will make the tepees. You will be good wives."

Then she spoke to the girls who weren't married. "You will be pure until you get married. When you do get married, you will always be faithful to your man. . . ." [One can't help noting here that this is in diametrical contrast to Silko's version, at least, of the "fertility goddess" Yellow Woman, whom she claims serves as an exemplum for traditional Pueblo women freely having premarital sex with multiple partners.]

This is the way Flora Driving Hawk would tell the White Buffalo Calf Woman legend. It differs from the way a man would tell the story, barely noting facts important to the men, but stressing those aspects vital to the women. (3-4) [But contrast this gendered reading of the story, and Lakota culture, with that of Mary Brave Bird!]

|

|

|

.gif) Note on Zitkala-Sha

Note on Zitkala-Sha  (early Nakota writer & activist, 1876-1938): (early Nakota writer & activist, 1876-1938):

|

| | —Interestingly, her book Old Indian Legends (1901)

consists mostly of stories about Iktomi (the trickster) and contains no treatment of White Buffalo Woman. This seems rather ironic because Z-S was

one of the first Native "women of power," writing and speaking frequently on the U.S. government's corruptive mistreatment of Native

Americans and clamoring for Indian suffrage. She did write such a

treatment—called "Buffalo Woman"—but it remained unpublished until long after her death. (You can read it on Google Books; do a search for "Zitkala-Sa" and Dreams and

Thunder, the recent collection [2001] in which it is published.) This version seems more distinguished by its addition of many "literary" details than

anything else. She doesn't mention the Sacred Pipe; but she does reference WBW's marriage to the South Wind (part of the Wohpe story

cycle). . . Zitkala-Sha actually seemed more fascinated by one of WBW's Pleiades sisters,

Blue-Star Woman, whose name is given to the title character of one of her most well-known (and politically aware) stories:

online: The Widespread Enigma Concerning Blue-Star Woman

|

| Postscript: Arvol Looking Horse and the Return of the White Buffalo |

|---|

As the current Pipe Keeper of the Lakota, Arvol Looking Horse (Mniconjou Lakota) has been involved for well over a decade in a

controversy regarding the birth of white buffalo calves in the U.S. and their possible relation to prophecy. While he has dubbed

some white buffalo appearances as fakes, Looking Horse has also played up these births in general as prophetic of an apocalyptic "new day"

that smacks of Ghost Dance messianism, which itself is derived from Christian eschatology. (That is, much of the prophesying below implies an "end-of-linear-history" radical break that is fairly alien to the traditional

Lakota worldview, which tends to conceive of time as a circle.) To carefully express my own view of the matter, let me just say that some

Euro-American New Age people are really

eating this up, tempting certain Lakota to join what Vine Deloria calls the "New Age/Indian medicine man circuit" and to succumb to

capitalist temptations. (Traditionally, the "Lakota way" included no urge to proselytize because of a consciousness that it was based upon

a specific history, geography, and

people. In sum, it doesn't "travel well," and it has [should have] nothing for sale. [By now I'm really haranguing all those (usually Anglo) fakers on the web

who claim that their new name—Really Brave Eagle or Snowdrop Maiden—came to them in a vision and that they have "just the authentic

Indian sweat lodge weekend retreat on sale for you!" See the "Selling of Indian Culture" link below.])

Here are some representative links regarding this phenomenon:

Buffalo Messengers Buffalo Messengers

Statement from Chief Arvol Looking Horse, 19th Generation Keeper of the Sacred White Buffalo Calf Pipe Statement from Chief Arvol Looking Horse, 19th Generation Keeper of the Sacred White Buffalo Calf Pipe

Miracle, the Sacred White Buffalo: A Gift to the Hearts of All People Miracle, the Sacred White Buffalo: A Gift to the Hearts of All People

[Arvol Looking Horse support letter] [Arvol Looking Horse support letter]

| |

We have a prophecy which I've heard since my early years of the age of twelve that someday the spirit of the White Buffalo Calf Woman would

stand upon Mother Earth. At that time, great changes would happen to Mother Earth. In 1994, Miracle was the first white buffalo to be born.

Now, eight have been born, signifying a great urgency!

|

Miracle, the White Buffalo (nativeamericans.com) Miracle, the White Buffalo (nativeamericans.com)

White Buffalo Calf Woman Promised to Return (Stockbauer) White Buffalo Calf Woman Promised to Return (Stockbauer)

The White Buffalo (complete with flute music) The White Buffalo (complete with flute music)

| |

Naturally, an assortment of wealthy collectors and modern-day Barnums have also shown an interest in the calf. Early on, rock star Ted Nugent, who penned a song about a white buffalo, offered to buy Miracle.

|

.gif) Finally, a sobering antidote to the gesture in some quarters of turning Lakota ceremonialism into some crosscultural, ecumenical religion:

Finally, a sobering antidote to the gesture in some quarters of turning Lakota ceremonialism into some crosscultural, ecumenical religion:

The Selling of Indian Culture: The White Buffalo Calf Pipe Commercialized (Dakota/Lakota/Nakota Human Rights Advocacy Coalition)

| Is this what it's all come to? The Cher "Halfbreed" Barbie => |  |

Hmmm. Having thought I was done with this section, I came across a passage in Winona LaDuke's All Our Relations: Native Struggles for Land and Life (South End Press, 1999):

Hmmm. Having thought I was done with this section, I came across a passage in Winona LaDuke's All Our Relations: Native Struggles for Land and Life (South End Press, 1999):

| |

It is said that should the Earth, the mother of all life, ever be shaken to crisis by the people living upon her, then the White Buffalo Calf Woman will return. In the Summer of 1995, a white buffalo calf was born in southern Wisconsin. Called "Miracle," the calf has brought new hope to the buffalo nation and the buffalo peoples of the Great Plains. The return of the White Buffalo Calf Woman symbolizes the beginning of a new time, a new era, and with it the promise of restoration. (140) |

|

|

.gif)